Examining the roots of biased reporting on Africa

Insensitive Reporting

Writing betrays the notion

of subjects as subhuman

Creating Distance from Subjects

Examining the roots of biased reporting on Africa

Insensitive Reporting

Writing betrays the notion

of subjects as subhuman

Creating Distance from Subjects

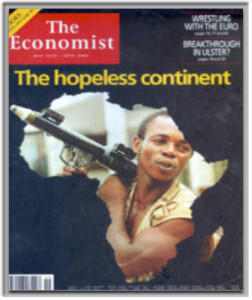

The cover of the venerable weekly magazine, the Economist in May 2000 said it all. Inside the outline of the continent of Africa, the magazine showed a photo of a young soldier with a rocket launcher slung over his shoulder. Above it was the headline, “The hopeless continent.”

This example, though extreme, is not unusual in the attitude foreign correspondents take when covering Africa. It is seen as one endless loop of famine, disease, chaos and wanton violence. Correspondents arrive looking for the thrill of their careers and are only too happy to chase the goriest, most devastating story. They tend to write these accounts with all the verve and poetry they can muster.

To be fair, there is good reason for this negative coverage. Africa has had more than its fair share of cartoon dictators, senseless wars and plagues wrought by nature. Reporters have followed the mantra of “if it bleeds, it leads,” for years and one should not expect the reporting on Africa to be any different. Journalists on the continent are under no obligation to write soft, feel good stories when so much despair still exists.

But a close observer of media coverage of Africa will note that there is something different at work on the continent. Reporters seem all too willing to take on a specialized reporting style that strives for poetry but lacks humanity. Take an October 2013 incident when a rickety boat carrying hundreds of migrants from Libya sank on the way to Lampedusa, an island located off the coast of Italy. The tragedy claimed the lives of over 300 people.

An event of this magnitude hasn’t been recorded in many years despite the fact that many migrants from the Middle East and Africa have taken the same perilous path seeking better lives. What was so significant about this tragedy is the fact that it was covered extensively. One of the media outlets which devoted some space for coverage was The New Yorker. In an article penned shortly after the incident, a staff writer, Sarah Stillman, painted an image of the people who lost their lives during the tragedy. Below is how she opens her piece.

“ At first, the drowning men and women were mistaken for seagulls. Early Thursday morning, local yachters off the southern Italian island of Lampedusa still had no idea that a ship carrying some five hundred African asylum seekers had just gone down in the water nearby. Hearing high-pitched cries, they looked out to sea to find that the source of the noise wasn’t birds (as they’d first assumed) but Eritrean migrants shouting for help, their bodies thrashing. A large portion were women and children fleeing conflict and poverty by way of Libya, only to be hastily drowning, within eyesight of the Italian shoreline, in the same waters they’d hoped would rescript their lives.”

Comparing the shrieks of the drowning to seagulls paints a vivid picture, but it might not have been chosen by a reporter covering another disaster. To most readers it would have seemed out of place in coverage of the recent ferry tragedy that has claimed the lives of dozens off the coast of South Korea. It is similarly telling that the first reaction to the incident is shown through the eyes of Italian yachters. The survivors and victims’ families will have to wait to tell their stories.

Such unconscious distancing of the subject occurs often in Africa coverage where reporters often seem to arrive on the continent, figuratively, wearing the pith helmet of explorers from a bygone era.

Incognizant racism

In 1993 the usually diligent writer and historian Robert Kaplan travelled to West Africa for the Atlantic to write about a “demographic time bomb” about to detonate in the region leading to overpopulation and chaos. That, of course, never happened. But his descriptions of the young men he saw in the Ivory Coast was telling of his outlook.

“ Each time I went to the Abidjan bus terminal, groups of young men with restless, scanning eyes surrounded my taxi, putting their hands all over the windows, demanding ‘tips’ for carrying my luggage even though I had only a rucksack. In cities in six West African countries I saw similar young men everywhere—hordes of them. They were like loose molecules in a very unstable social fluid, a fluid that was clearly on the verge of igniting.”

It is not unusual for a westerner to justifiably feel swarmed by hawkers and street vendors when he or she enters a major African city. But the description of “hordes” of young men with “restless” and “scanning eyes” who behaved like “loose molecules” is clearly dehumanizing. Undoubtedly Kaplan attracted more attention from the young people because he stood out as a foreigner, but he also projected his fear onto the people who surrounded him.

Would an African writer have described the scene differently? Perhaps the “hordes” of young men would have looked more like small groups. Perhaps the “scanning eyes” would have looked to an African reporter like a good salesman keeping his eyes peeled for other customers.

In 2011, Ivory Coast was once again in the news after a standoff between the two contesting presidential candidates that lasted more than four months. Once the dust cleared, hundreds were dead and more than 1 million displaced. On April 11 of that year, the former president Laurent Gbagbo was arrested and rightfully elected president Allesane Ouattara was able to take the reins of power. At the hight of the civil war, I talked by phone to Ofeibea Quist-Arcton, who is a journalist and broadcaster originally from Ghana who reports for National Public Radio on issues and developments related to West Africa.

After discussing the political environment and the violence, I asked Quist-Arcton how safe she felt in such circumstances. Coincidentally, she was reporting in Abidjan, the same city Kaplan visited during a time of peace. She said even during the time when there was conflict, “I’m an African woman so I blend in much more easily than David being a European man and a tall man that is easy to target.”

She was referring to David Smith, who is the Guardian’s Africa correspondent. Smith was also on the line for this phone interview. I asked him about his safety during the reporting. He said: “I was certainly on my guard because of numerous reports and warnings from other journalists on the ground before me at the same time. A hotel which I stayed in last month was targeted by some armed groups and some people were kidnapped in there and the journalists that were there had a very difficult emotional time some of them were in the end taken from there by the French military.”

I include this example (click link for report) not to celebrate Quist-Arcton or diminish Smith as reporters, they’re both excellent, but show how different the same scene can look to people of different backgrounds. Even in the relative chaos of a war, Quist-Arcton, a native African, was able to move about freely and gave a different angle on the stories. It is doubtful that she saw the Ivory Coast conflict as the inevitable ignition of an unstable community as Kaplan had. Instead, she saw the human element, the ethnic, religious and colonial history and many other things that made up the rich stew of Ivory Coast.

A corollary to this is what Don Heider in his book “White News: Why Local News Programs Don’t Cover People of Color,” calls “incognizant racism.” Heider said that inclusive coverage becomes the victim when journalists have a predetermined belief of what’s expected of them.

“ Incognizant racism occurs when journalists produce news products day-in and day-out that simply exclude any meaningful coverage of racial-ethnic communities. In some cases this may actually be a conscious and intentional act, but at least in the newsrooms I have observed, it is not an overt process. It is the result of dozens of daily decisions, of years of training and practice, of decades of cultural orientation, and of a well-documented history of systematic and institutionalized neglect. It is both an individual and collective process.”

Many foreign correspondents exhibit incognizant racism when they arrive on the “hopeless continent” prepared to paint a picture for their readers, viewers or listeners. An African perspective may not be as flashy, but it can often add nuance and uncover hidden stories. Heider shows the same is true covering minority communities in the United States.

Doom and Gloom

Disaster chasers showing one side of the story

Painting a Grim Picture

In 2005, the New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristoff pointed out that, at the height of the crisis in Darfur, the major television news networks had barely reported on it. For the entire year, ABC News dedicated 18 minutes to Darfur, NBC devoted 5 minutes and CBS spent a paltry 3 minutes. By contrast, the Martha Stewart trial received a combined 130 minutes of coverage.

If the genocide in Darfur received barely a yawn from the news outlets, other issues barely stood a chance. Kristoff wrote that only one network had even bothered to send an anchor to Africa that year. It was ABC which sent Diane Sawyer there to interview Brad Pitt.

When Africa does receive coverage it generally comes in the form of doom and gloom. This is what CNN Africa correspondent, Jeff Koinange, referred to during a panel discussion among African journalists as the 4 D’s — Death, disease, despair and desperation. Even when news about poverty, AIDS and corruption are reported, most local reporters agree that they are reported without context or the same specificity that would be used to cover a tragedy in the West.

In another discussion about the coverage of the continent, Kristoff reveals that it is very difficult to market stories on Africa. In 2006, CNN’s Anderson Cooper for instance prepared a live report on the Congo but in turn lost 20 to 30 percent of his audience by doing that.

One of the most potent examples I have come across comes from the New York Times Pullitzer Prize winning East Africa correspondent Jeffery Gettleman. Reporting about a massacre in Sudan, Gettleman wrote:

“ The trail of corpses begins about 300 yards from the corrugated metal gate of the United Nations compound and stretches for miles into the bush.”

Most readers will, rightfully, shake their heads in disgust at this unimaginably horrific scene. But to the seasoned journalists, something is awry. A trail of corpses stretches for miles? Did Gettleman attempt to count the corpses? Isn’t the first rule of journalism to collect facts? Could a Pullitzer Prize winner simply see this “trail” and not investigate it further? Imagine Gettleman had been working in Tampa, Fla.—he previously worked at the Tampa Bay Times–and came back with a similar story. The first question his stunned editor would ask is “how many bodies were there? I need details about cause of death?” In Africa, such journalistic principles fall by the wayside. It is assumed there will be trails of corpses. Editors accept it. Readers accept it. Reporters can’t be bothered to be too specific. They’re there to paint pictures with words, after all.

Empathy vs. Sympathy

The power of walking in another’s shoes

Understanding “the Other”

Pity vs. Understanding

In an interview conducted by Foreign Policy Interrupted, a blog which aims to create space for women to share their voices on international issues, Nigerian journalist Alexis Okeowo wrote about the importance of empathy vs. sympathy. The simple act of telling stories from another person’s point of view is very crucial when reporting. Okeowo argues that “very few people want to be pitied. They want to be understood. That distinction makes all the difference in your reporting and writing. It elevates Africans out of caricature and stereotype into human beings, as full as anyone in the United States and Europe.”

This attitude surpasses boundaries and applies to all writing. Africans have too often been defined and portrayed in ways they don’t agree with because they have not had control of media.

There is also the barrier of understanding. Few western reporters bother to learn local languages or much about the culture beyond the broad brush strokes. In a 2014 Op-Ed published by al-Jazeera, Nanjala Nyabola, a Kenyan studying at Harvard Law School points out that English and even Swahili are languages used most often in formal settings by many East Africans. For true understanding of what is happening, an observer needs to hear conversations in languages like Kikuyu or Dinka.

“ The use of poorly translated or contextualized concepts of hardened constructs in place of malleable ones is thus an integral part of the broader frustration that Africa just isn’t being heard right,” Nyabola wrote. “Yes, this person says that Tribe X is responsible for issue Y, but are they just using that as shorthand for a more complex phenomenon, like the interrelationship between class, ethnicity and power?”

These misunderstandings result in complex conflicts like those in Sudan, Rwanda or the Central African Republic being described in very simple terms as issues of Muslim versus Christian or tribe versus tribe, Nyabola wrote.

White Savior Complex

Africans are generally in the position where foreign writers, documentary film makers and others tell their stories for them.

This phenomenon can be viewed through media which has regularly told African stories through the prism of “white saviors.” The examples of this are numerous. The conflict in Sudan was dramatized on the big screen as “The Machine Gun Preacher,” the story of a white missionary who fought rebels in the region.

The famine in Ethiopia was made into a movie, “Beyond Borders” starring Angelina Jolie.

Even the movie about the Rwanda genocide, “Hotel Rwanda” had room for a white protagonist, a U.N. peacekeeper, and white antagonists played by the slow-footed, calculating world leaders who refused to intervene.

-

1

Angelina Jolie starred in “Beyond Borders,” a movie about the famine in Ethiopia.

-

2

A poster from “Blood Diamond,” starring Leonardo DiCapro.

-

3

Don Cheadle and Nick Notle starred in “Hotel Rwanda,” a movie with a white protagonist U.N. peacekeeper.

-

4

A scene from “The Machine Gun Preacher,” the story of a white missionary who fought rebels in the region.

Hollywood, like the work of many foreign journalists, has difficulty putting fully-formed, complex African stories at the center of a narrative. For that reason, it seems vitally important that, like Okeowo urged, Africans tell their own stories. From Cairo to Cape Town, the African media is thriving like never before but is also under attack. In the past two years, newspapers have been shut down by government orders in the Ivory Coast, Uganda and Liberia. Many other countries including Ethiopia, Eritrea and Sudan have virtually no independent media at all operating domestically. But at the same time, bloggers and brave journalists are staking out new ground and reporting untold stories. One example is Radio Erena, a proudly independent radio that is based in Paris broadcasting news to Eritrea via internet. It reports the news from within and outside Eritrea on a daily basis and through a large network of stringers and informants.

With this type of work, Africans will not be forced to rely on foreign correspondents to tell their stories. The recently deceased Nigerian poet and novelist may have said it best in his inimitable way:

“ Until lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”