A Melancholic Day

World Press Freedom in the Horn of Africa

Bumps in the Road Ahead

A Melancholic Day

World Press Freedom in the Horn of Africa

Bumps in the Road Ahead

On World Press Freedom day, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) released its annual list of the best and worst countries as it relates to press freedom. The usual suspects, Eritrea and Equatorial Guinea, were singled out in a list of the 10 worst countries for censorship. Many other African countries received failing marks.

On World Press Freedom day, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) released its annual list of the best and worst countries as it relates to press freedom. The usual suspects, Eritrea and Equatorial Guinea, were singled out in a list of the 10 worst countries for censorship. Many other African countries received failing marks.

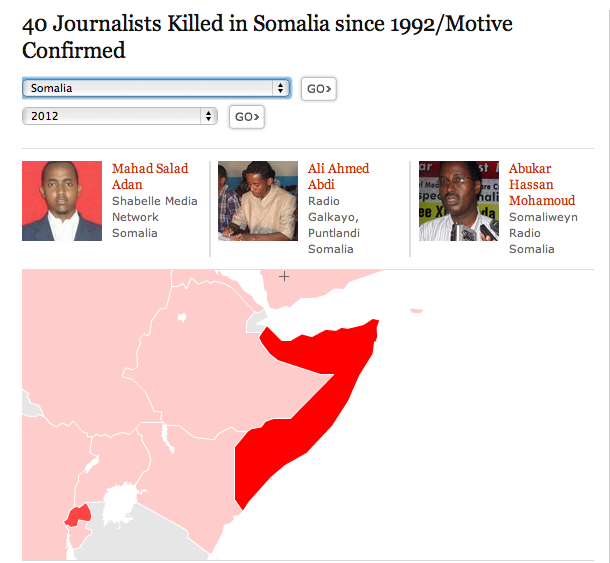

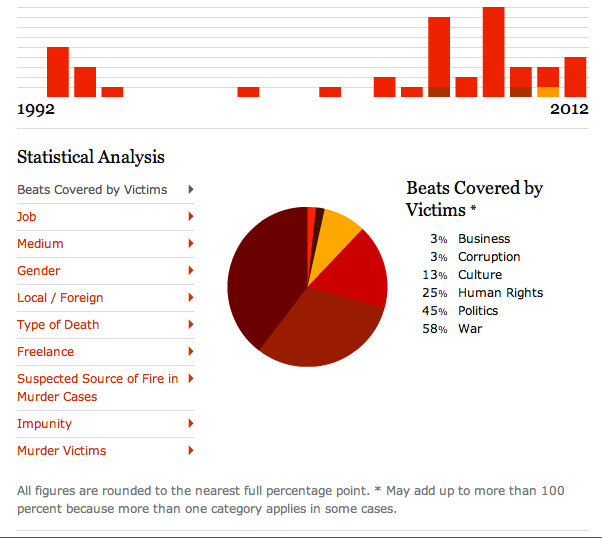

Since, in most cases, national security is the excuse given to counterbalance arguments regarding press freedom, it got me wondering. As I was reading the list published by CPJ, I was struck by a notable omission. Doesn’t a free press need some semblance of stability in order to operate? And yet Africa’s most notorious failed state, was not listed. Somalia, a country destroyed and consumed by conflict since, arguably, the turn of the last century somehow avoided mention. In the past 20 years, 40 journalists have been killed in Somalia (since 1992). Yet, in spite of threats posed by terror groups and the worst drought in 40 years, Somalia still manages to allow a space for journalists to report on issues that matter. Southern Somalia with its Transitional Federal Government supported by external actors such as the African Union peacekeepers is only truly able to control the capital city, Mogadishu.

Since, in most cases, national security is the excuse given to counterbalance arguments regarding press freedom, it got me wondering. As I was reading the list published by CPJ, I was struck by a notable omission. Doesn’t a free press need some semblance of stability in order to operate? And yet Africa’s most notorious failed state, was not listed. Somalia, a country destroyed and consumed by conflict since, arguably, the turn of the last century somehow avoided mention. In the past 20 years, 40 journalists have been killed in Somalia (since 1992). Yet, in spite of threats posed by terror groups and the worst drought in 40 years, Somalia still manages to allow a space for journalists to report on issues that matter. Southern Somalia with its Transitional Federal Government supported by external actors such as the African Union peacekeepers is only truly able to control the capital city, Mogadishu.

A power struggle with Islamist militant groups such as Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam continue to render large swaths of land in the south no-go areas. And yet, amidst the anarchy, journalists still roll out reports on social and political issues from the country. They are confronted with restrictions, intimidation and physical threats on the ground on a daily basis. The south is a much different environment compared to Puntland in the northeast and Somaliland which has had a peaceful free and fair elections and presents a fair opportunity and space for the press. For example, recently a hopeful voice was heard after Voice of Peace radio director Awke Abdullahi was released. He said he will never abandon his commitment as a journalist and defend his community despite the fact that he just endured two months of detention in prison. This proves that there are challenges but also marks as a victory for the freedom of the press.There are additional reports of intimidation of journalists in Somaliland but what is striking is that these reports are being confirmed from Somalia by journalists who are allowed to practice in their country. Mogadishu is not an exception in this case and it just goes to show that the media still faces dire challenges ahead. I take my hat off to the people who continue to churn out the daily news reports in Somalia even when the news is full of tragedy.

A power struggle with Islamist militant groups such as Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam continue to render large swaths of land in the south no-go areas. And yet, amidst the anarchy, journalists still roll out reports on social and political issues from the country. They are confronted with restrictions, intimidation and physical threats on the ground on a daily basis. The south is a much different environment compared to Puntland in the northeast and Somaliland which has had a peaceful free and fair elections and presents a fair opportunity and space for the press. For example, recently a hopeful voice was heard after Voice of Peace radio director Awke Abdullahi was released. He said he will never abandon his commitment as a journalist and defend his community despite the fact that he just endured two months of detention in prison. This proves that there are challenges but also marks as a victory for the freedom of the press.There are additional reports of intimidation of journalists in Somaliland but what is striking is that these reports are being confirmed from Somalia by journalists who are allowed to practice in their country. Mogadishu is not an exception in this case and it just goes to show that the media still faces dire challenges ahead. I take my hat off to the people who continue to churn out the daily news reports in Somalia even when the news is full of tragedy.

Shifting gears, in an Op-Ed on the New York Times, Mohamed Keita, the Africa advocacy coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists, made interesting points about the relationship between the press and economic growth. As the presence of China increases on the continent to compete for Africa’s natural resources, China is pushing the need to focus only on positive news of achievements by governments. This approach used by most governments on the continent desensitizes and misinforms the audience. People look for the media to stick up for their interest and bring about reforms on various social and political issues. In addition, state-run media only serves the interest of governments and does not leave room for holding authorities to account.

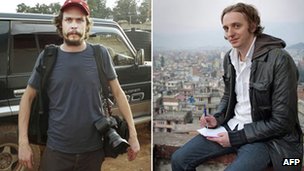

In the opinion piece, Ethiopia’s and Rwanda’s economic growth and suppression of media was used as an example to show a growing trend. Ethiopia is also involved in a disturbing type of systematic squashing of the media as the government continually uses the banner of terrorism to imprison journalists and squash dissent. Eskinder Nega, an Ethiopian journalist who decided to stay in the country and report from the ground despite media crackdown by the government is an example of one of the people who are facing imprisonment for inciting terrorism and could face a death penalty if found guilty in a hearing scheduled later in May. Foreign journalists aren’t immune to the terrorism laws being used against journalists. A recent arrest and an eleven year sentence handed down to Swedish journalists, Martin Schibbye and Johan Persson, also brings up this concern of how governments use terrorism laws. The reporters were captured with rebel groups from Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) while documenting the groups’s activities. The rebel groups are part of many opposition movements working against the Ethiopian government.

There are other types of difficulties facing the press in African countries. For instance, although Rwanda’s relations with China and economic growth were mentioned in the article in relation to stifling the press, post-genocide issues have had a dire impact on how journalists go about reporting. In recent news, the supreme court of Rwanda showed some sign of leeway when the sentence of two journalists Agnes Uwimana Nkusi and Saidati Mukakibibi, was reduced from seventeen to four years and from seven to three respectively. What makes the charges on the women unfair is the fact that pro-government tabloids with messages inciting violence get away with printing quotes such as this: speaking against opposition, “We do not exaggerate when we say the ordinary Rwandan in the rural areas still thinks when your tribesman wins the elections you have carte blanche to dust off your machete, hone it and cut up your neighbor from the different ethnic group, or throw him into the river, or carry out pogroms.” This is as incendiary as the rhetoric that helped fuel the genocide in 1994 and it should not be allowed in the new Rwanda.

This double standard is bound to come back to haunt the justice system in the long run. I’ve had similar discussions with Rwandans who are concerned by the legacy the genocide has left in terms of freedom of expression. Nadege Uwase, the Executive Director of Global Issues Leadership Development (GILD), is a genocide survivor and deeply understands the conditions in the country from personal experience. She expressed her concerns during the election in 2010 shortly after visiting Rwanda. Talking about her visit, “I was thoroughly disappointed by party opposition leaders. They were hardly visible. I think my country needs to get to a point where one can have a political argument, especially about our government’s policies without fear of life. Because of the genocide legacy, we are not quite there yet, our political climate does not allow that. With that legacy, it is hard to encourage civil discourse, which we desperately need.”

The fact remains that the media has been used to distract people from real problems and against populations in a negative way. However, this extreme example of Rwanda is also used to justify atrocity against journalists. Sure the media was used to turn clans against each other during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. Philip Gourevitch, the author of “We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families” notes in this book review, “the dead had seen their killers training as militias in the weeks before the end, and it was well known that they were training to kill Tutsis; it was announced on the radio, it was in the newspapers, people spoke of it openly.” But as societies learn how to use their voice to build up their communities and come out of traumatic experiences, in time this argument also loses ground.

Eritrea is a unique case since independent media has been shut for over a decade. Countering the CPJ report, in an interview with the Voice of America, Dawit Haile from the Eritrean embassy in Washington D.C. said that the report is “groundless.” He said, “there are various and many types of satellite dishes that are available through the country, but also the countryside – also the city is filled with internet cafes, and people read all kinds of information.” It’s true, the public mostly in urban cities have access to satellite dishes allowing them to enjoy international TV programs. Unfortunately, those programs don’t inform them about their own country. Since there is no independent media and the list puts Eritrea first for censorship, I would like to briefly mention the use of Internet. Ironically, there is no record of internet censorship or filtering system. In fact, I’ve come across social media groups inside Eritrea allowed to freely express their opinions. The major stumbling block for internet users in the country is a slow bandwidth speed, 128K, and can be regarded as equitable for Africa. In Eritrea, education is a priority and internet access without education is meaningless.

An Open Society Foundation’s report by Iginio Gagliardone and Nicole Stremlamu, titled “Digital Media, Conflict and Diasporas in The Horn of Africa,” found out that even though Eritrea was the last country to get an Internet connection in Africa in 2000, “ in 2010 it registered the highest percentage of internet users in the Horn (5.4 percent).” The research, also notes that communities living in the United States and Europe produce and consume news online. The Internet undoubtably provides a medium where the diaspora can engage and talk about issues in regards to the country. However, there are major fallouts even within this medium. As online information overwhelms the audience it is also getting hard to differentiate facts from fictitious reports. A recent example is when unconfirmed rumors started swirling around online, mainly by opposition sites claiming the Eritrean president was terminally ill or even dead. Some outlets went as far as saying that tanks were in the capital, several military generals were arrested and there’s a coup attempt. This reckless and sensational tabloid-style reporting went on for a week even grabbing the attention of international media outlets until the president held an interview on Eri TV, the state-owned media outlet. Although it’s not the first time that online outlets have exaggerated and fabricated news, this specific incident is an indication that there is a need for independent media in the country. The only positive outcome from this incident was the fact that Eritreans were able to engage in civil discourse which is a rare commodity because of how polarizing the political condition of the country has become.

Overall, the fundamental principles of journalism are universal and challenges in the region will take time to show progress. This should also remind us that there is a need to celebrate and remember brave journalists on the continent who risk their lives, face harassment, imprisonment and pay the ultimate price while on duty. Difficulties can only be met with increased participation of African journalists who abide by strict codes of ethical behavior and are committed to informing the public in order to improve the lives of the people. I will end post with a quote by George Ayittey, a Ghanian economic professor, an author and president of Free Africa Foundation in D.C. : “Real reform starts with INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM – freedom of expression, of the media, etc. Reform must come from WITHIN to be sustainable, not dictated from the outside. It is the PEOPLE who must make their own case for reform.”

I would also like to recommend an interview I was fortunate enough to conduct with a group of Pakistani journalists on Global Journalist, a show which also produces a multimedia content for its website and broadcast on KBIA.org, Central Missouri’s NPR affiliate. We discussed the challenges journalists face when covering the often turbulent events in their country and what needs to be done to improve press freedom. As they share their experiences and give recommendations, it draws parallels to the challenges in highly volatile areas in Africa.