Mutiny Within a Blink of an Eye Or A Ticking Time Bomb?

Mali’s Coup

Mutiny Within a Blink of an Eye Or A Ticking Time Bomb?

Mali’s Coup

In the past two months, West Africa has witnessed an unprecedented security threat as several governments were caught in the grips of coups or attempted coups. As Guinea-Bissau soldiers arrest the nation’s Prime minister over a suspected coup, Mali’s new interim civilian president got sworn into office last Thursday, after a 27 days long coup that has puzzled the International Community. Was Mali’s coup a surprise? Or does it have roots deeper than just a junta composed of low-ranking officers deposing a sitting president? And most importantly, how should other African governments avoid becoming the next victims of lawlessness?

In the past two months, West Africa has witnessed an unprecedented security threat as several governments were caught in the grips of coups or attempted coups. As Guinea-Bissau soldiers arrest the nation’s Prime minister over a suspected coup, Mali’s new interim civilian president got sworn into office last Thursday, after a 27 days long coup that has puzzled the International Community. Was Mali’s coup a surprise? Or does it have roots deeper than just a junta composed of low-ranking officers deposing a sitting president? And most importantly, how should other African governments avoid becoming the next victims of lawlessness?

Let’s start with a bit of context. In January of this year, Malians were already voting, voting with their feet that is. According to aid agencies, over 20,000 Malians fled into neighboring countries prompted, in part, by the uncertainty that followed a massacre of 82 Malian soldiers in the North. In this case, the Tuareg rebels utilized Al-Qa’ida methods including slitting the throats of soldiers and distributing the horrific images to the outside world.

The group at the heart of Mali’s chaos is demanding the creation of a new state in the northern provinces of Mali to be governed by Sharia law, the Tuareg rebels National Movement for the Liberation of Azwad (MNLA). This militant group is said to have joined forces with Ansar Dine, another Tuareg rebel group with ties to extremism. With the help of the latter rebel group, the chaos has escalated to eventually pose a regional threat.

However, long before the alliance of Tuareg rebel groups, according to a report titled “Global Jihad Sustained Through Africa,” by The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), Mali had already been victimized by terrorist activities. In February 2008, gunmen attacked an Israeli Embassy in Mali’s capital. In another incident, in August of 2010, two spanish aid workers were kidnapped in neighboring Mauritania and freed in Mali after nine months. Following that, in September of 2010, Mauritania decided to send its aircraft to attack militants who had kidnapped seven foreigners near the Niger-Mali border.

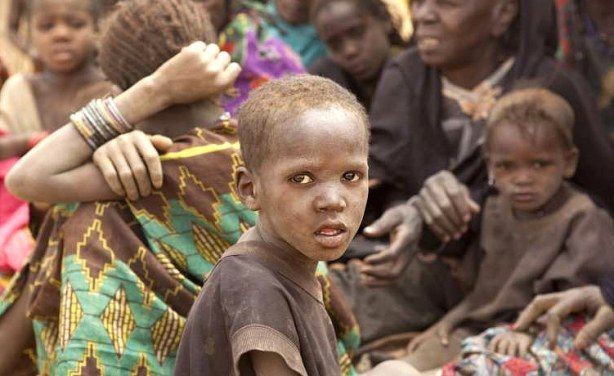

Mali was well aware of this. Despite Malian President Amadou Toumani Toure dubbing the turmoil in the north as “Other people’s war,” the country did recognize the threat to its security. In fact, in April 2010, it teamed up with Mauritania, Niger and Algeria and signed a treaty to combat terrorism in the region. But abductions continued and continue to this day. A trend demonstrably pointing to Al-Qa’ida’s thuggish strategy to capitalize on vulnerable individuals to generate income as ransom payments are funneled for rescue. The rebels continue their rampage while over 200,000 Malians flee looting, hunger and complete anarchy.

So, how could ATT’s government be oblivious when there were vivid warning signs in the North Sahel region? Leading up to March, it appeared to be business as usual for the president. He not only ignored the chaos in the north showing little to no attempt to suppress the rising panic and anger of his soldiers and junior officers, but also ignored the fact that they were victimized by the rebels. There were even reported incidents of Malian soldiers being unable to pursue rebel groups due to a lack of petrol available for their vehicles.

This recipe for disaster prompted the soldiers to act the only way they know how to: Mutiny. The junta, National Committee for the Re-establishment of Democracy and the Restoration of the State (CNRDRE), decided to take matters into their own hands and embarked on a misguided mutiny that dismantled peace and constitutional order in the country. What a wake up call it was for the president who was chased into hiding just weeks away from scheduled elections.

At present, Mali has a fragile future. Dioncounda Traore, the seventy-year-old newly sworn-in civilian president, with his doctorate in mathematics, has been given an opportunity to solve the difficult equation of holding national elections within forty days. The first question one might ask is: how can elections even be held when fully 65 percent of the country is not under the control of the central government? During his inauguration ceremony, he vowed that there would be no hesitation “to wage a total, relentless war” against what he calls the “invaders.”

Waiting in the wings is the former coup leader Capt. Amadou Sanogo who has expressed an interest in returning to power if he feels the urge. Today, Mali is at the mercy of an unpredictable political atmosphere while thousands of its citizens are displaced and desperately awaiting a return to normalcy.

Waiting in the wings is the former coup leader Capt. Amadou Sanogo who has expressed an interest in returning to power if he feels the urge. Today, Mali is at the mercy of an unpredictable political atmosphere while thousands of its citizens are displaced and desperately awaiting a return to normalcy.

What can other African governments with similar militant group threats in remote regions learn from Mali? I think it is clear to see that dismissing or simplifying militant threats will not only embolden militant efforts but also put leaders in a compromising position. The crux of the matter is that after recurring extremist attacks, leadership attitudes have changed in the continent. It is up to African governments to take the helm of leadership and find the courage to work together. Even one unstable region, one dissident group or suicide bomb attack in a community is too many to ignore.