Eritrean Culture on Trial: Assimilation Gone Awry

Eritrean Culture on Trial: Assimilation Gone Awry

As a former Missourian and an Eritrean immigrant, I was heartbroken when I came across the April 15th St. Louis Post Dispatch front page story detailing the statutory rape case against an Eritrean immigrant in St. Louis who impregnated a 12-year-old. As I scanned through the story, I spotted several ambiguous parts which begged for perspective. In today’s blog entry, I will try to explain this clash of new immigrant adapting to the cultural norms of his or her adopted society. I’ll also trace the cultural roots of traditional practices of the Kunama ethnic group in reference to the case and I will take a quick look at the bizarre birthday, January 1st, that all of the immigrants involved in the case share.

Let’s start with the good news. Despite hostile reactions towards immigration issues plaguing the country, especially as the rhetoric around election season heats up, St. Louis has proven to be more than just a place for resettling immigrants. The International Institute of St. Louis’ president and CEO Anna Crosslin, made a point of letting residents know that refugees have opened about 300 small businesses bringing more than $100 million in the region in different forms varying from job creation to spending profits. Therefore, for 20,000 refugees sponsored by the institute, it has become a place they call home. These stories are constant reminders of how the area has not only embraced immigrants who came to the U.S. looking for protection but also created an environment for them to thrive.

I’d also like to point out the inspiring successful Eritrean-American migrant stories before talking about the challenges and complexities surrounding this unfortunate matter. St. Louis is home to Dr. Ruth Iyob, a noted Eritrean intellectual, an associate professor and research fellow in the Center for International studies at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. Dr. Iyob is a noted scholar who wrote, perhaps, the definitive political science account of Eritrea’s road to freedom. It was mandatory reading when I was a student at Asmara University. St. Louis is also home to Mengesha Yohannes and his brothers who are celebrating the 27th anniversary of their restaurant Bar Italia, a successful Central West End restaurant with some Eritrean roots, serving mainly Italian food bringing to light a reminder that Eritrea was once an Italian colony.Those are the immigrant stories off the top of my head as evidence and example that, when afforded opportunities, Eritrean immigrants benefit the economic growth of their communities and, in turn, achieve the American Dream.

Nevertheless, some challenges put a strain on immigrants assimilating to a new area as is common in most cases. Hence, it is sobering to come across stories of newly arrived Eritrean immigrants who have gone through horrible ordeals to come to the U.S. just to find themselves struggling to adjust to yet another challenge in what they considered their new home. The Eritrean community in the St. Louis area have endured tragic losses in recent years. From young lives cut short in an unsolved homicide where the victim was a second generation twenty year old young Eritrean man, Romeo H. Teferi, to a report about a fifteen year-old young boy, Sahele Wodede, caught in the line of fire during an inner-city shootout. Such incidents demonstrate that crime is one of the major facts of life for new immigrants who, typically, find themselves living in dangerous neighborhoods as they try to carve out a life for themselves.

Nevertheless, some challenges put a strain on immigrants assimilating to a new area as is common in most cases. Hence, it is sobering to come across stories of newly arrived Eritrean immigrants who have gone through horrible ordeals to come to the U.S. just to find themselves struggling to adjust to yet another challenge in what they considered their new home. The Eritrean community in the St. Louis area have endured tragic losses in recent years. From young lives cut short in an unsolved homicide where the victim was a second generation twenty year old young Eritrean man, Romeo H. Teferi, to a report about a fifteen year-old young boy, Sahele Wodede, caught in the line of fire during an inner-city shootout. Such incidents demonstrate that crime is one of the major facts of life for new immigrants who, typically, find themselves living in dangerous neighborhoods as they try to carve out a life for themselves.

At the wheel of assimilation is a growing call for action by resettlement agents to curb cultural differences between the hosting community and immigrants. Nothing brings this challenge to the forefront as much as the case of the account of a statutory rape against an Eritrean immigrant which I mentioned at the outset of this piece. In this case the accused, Asannay Marbati, protested that having sex with a minor in Eritrea is acceptable, despite legal prohibitions of such traditional practices in Eritrea. I feel that it is important for the readers to understand that, contrary to the claims by the accused, in Eritrea, the legal age of consent is 18. The penal code of the country criminalizes all sorts of physical and sexual abuses against children. The law doesn’t take this issue lightly. In fact it penalizes offenders with harsh imprisonment for up to fifteen years depending on the severity of the sexual offense of minors below 15-years-old.

Similar to narratives heard about developing countries, Eritrea also faces fundamental legal challenges to this day. There is a culture-clash between traditional practices and modern laws and norms. However, it is important to note that Eritrea has made strides in abolishing harmful traditional practices in the country. For instance, in 2007 Eritrea abolished female genital mutilation (FGM), a common practice in the region and the continent as a whole. This issue is close to home for me since my mother, who serves as the head nurse in a government clinic, led campaigns against FGM and I was fortunate enough to witness exciting conversations among women who discussed for the first time the harmful effects of the practice. In addition to this, campaigns to combat traditional practices such as child marriage and arranged marriage are showing progress in Eritrea.

Similar to narratives heard about developing countries, Eritrea also faces fundamental legal challenges to this day. There is a culture-clash between traditional practices and modern laws and norms. However, it is important to note that Eritrea has made strides in abolishing harmful traditional practices in the country. For instance, in 2007 Eritrea abolished female genital mutilation (FGM), a common practice in the region and the continent as a whole. This issue is close to home for me since my mother, who serves as the head nurse in a government clinic, led campaigns against FGM and I was fortunate enough to witness exciting conversations among women who discussed for the first time the harmful effects of the practice. In addition to this, campaigns to combat traditional practices such as child marriage and arranged marriage are showing progress in Eritrea.

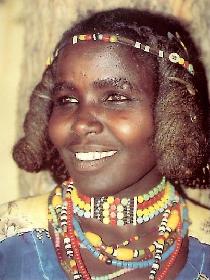

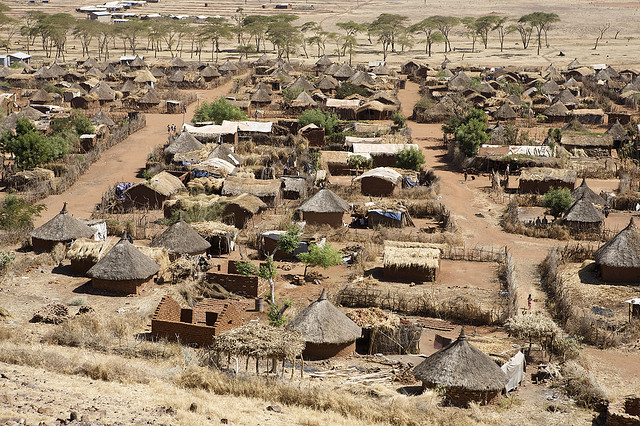

Another important factor to take into consideration when examining the St. Louis case is the cultural background of the Kunama ethnic group. Eritrea has nine ethnic groups and the Kunama make up 2% of the population. According to the late Dr. Alexander Naty, who taught Anthropology at Asmara University (I was one of the students in his class in 2001), an interesting fact about the Kunama ethnic group is that before converting to Christianity or Islam, their communities followed matrilineal lines creating higher social status for women in the decision making process of their communities. Dr. Naty also recounted oral Kunama testimonies from members of the Shila clan of how communities were safe havens for women in other ethnic groups who were persecuted for pre-marital pregnancies.

Another important factor to take into consideration when examining the St. Louis case is the cultural background of the Kunama ethnic group. Eritrea has nine ethnic groups and the Kunama make up 2% of the population. According to the late Dr. Alexander Naty, who taught Anthropology at Asmara University (I was one of the students in his class in 2001), an interesting fact about the Kunama ethnic group is that before converting to Christianity or Islam, their communities followed matrilineal lines creating higher social status for women in the decision making process of their communities. Dr. Naty also recounted oral Kunama testimonies from members of the Shila clan of how communities were safe havens for women in other ethnic groups who were persecuted for pre-marital pregnancies.

“In the past girls among the Tigre were not supposed to get pregnant unless they were married. Those girls who became pregnant without legal marriage were killed. One would imagine that this practice must have been adopted after the Tigre conversion to Islam. In any case, a girl became pregnant and she told about her pregnancy to her brother who did not want his sister’s death. They decided to flee to the land of the Kunama ethnic group. The girl delivered her child there. According to this Kunama oral tradition, members of the Shila clan trace their descent to this legend.”

This being the oral tradition passed in the Kunama ethic group, according to a report by the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, a research on the resettlement of Kunama refugees who lived in Ethiopian Refugee camps after fleeing a border conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia from 1998 – 2000, the report notes that it is common for minor girls as young as 13 or 14 to be married to older men. But in a surprise twist to the antithetical theories presented above, the same research notes that despite few opportunities given to girls for school:

This being the oral tradition passed in the Kunama ethic group, according to a report by the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, a research on the resettlement of Kunama refugees who lived in Ethiopian Refugee camps after fleeing a border conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia from 1998 – 2000, the report notes that it is common for minor girls as young as 13 or 14 to be married to older men. But in a surprise twist to the antithetical theories presented above, the same research notes that despite few opportunities given to girls for school:

“when a mother dies, her children join her mother’s relatives, even if the children’s father is still alive. Elderly women wield a great deal of authority over younger family members.”

Additional research on the Kunama community reveals that despite the continuation of poor traditional practices such as FGM and child marriage, some still remain matrilineal.

Last but not least, I would like to bring the bizarre coincidence noted in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch article that many immigrants share the same birthday, January 1st. This was not the first time I’ve heard of such reports. According to a report by The Sun, a British daily paper, immigration officers pick the birth date to migrants whose records were incomplete. But the claims of Suzanne LeLaurin from the International Institute of St. Louis suggest that it is because Eritrea doesn’t have a birth certificate or people don’t celebrate birthdays. She said “In many countries around the world, there is no such thing as birth certificates, there is no recognition of birthdays.” This claim has some merit. In rural regions, especially among nomad communities migrating from place to place, the knowledge to keep records may not exist. But Eritrea as a country keeps records of all its citizens in order to provide different governmental services. What might be the issue in this specific case is that since the group resettled in St. Louis came as refugees, it would be difficult to obtain original documents from government offices. What’s puzzling to me is how difficult could it be to prove someone’s age? I couldn’t help but think, aside from all the points mentioned, if authentic or conclusive evidence is not available to prove how old the girl is, shouldn’t there be an option to consult scientific experts? Not certain about technicalities and procedures but how about conducting ossification tests to verify if she is a minor or not? Even if it might not be a 100% conclusive, it is available. After all, we live in the 21st century where scientific evidence such as DNA tests are used to help solve too many criminal cases to count.

Last but not least, I would like to bring the bizarre coincidence noted in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch article that many immigrants share the same birthday, January 1st. This was not the first time I’ve heard of such reports. According to a report by The Sun, a British daily paper, immigration officers pick the birth date to migrants whose records were incomplete. But the claims of Suzanne LeLaurin from the International Institute of St. Louis suggest that it is because Eritrea doesn’t have a birth certificate or people don’t celebrate birthdays. She said “In many countries around the world, there is no such thing as birth certificates, there is no recognition of birthdays.” This claim has some merit. In rural regions, especially among nomad communities migrating from place to place, the knowledge to keep records may not exist. But Eritrea as a country keeps records of all its citizens in order to provide different governmental services. What might be the issue in this specific case is that since the group resettled in St. Louis came as refugees, it would be difficult to obtain original documents from government offices. What’s puzzling to me is how difficult could it be to prove someone’s age? I couldn’t help but think, aside from all the points mentioned, if authentic or conclusive evidence is not available to prove how old the girl is, shouldn’t there be an option to consult scientific experts? Not certain about technicalities and procedures but how about conducting ossification tests to verify if she is a minor or not? Even if it might not be a 100% conclusive, it is available. After all, we live in the 21st century where scientific evidence such as DNA tests are used to help solve too many criminal cases to count.

Overall, Missouri and the St. Louis area has been a welcoming home for immigrants who seek protection from war-ravaged areas of the world ranging all the way from Bosnia to the war-torn nation of Somalia. Immigrants seek rights and protections by coming to America, but that there is a flip side to that coin. Their adopted home will also hold them accountable for violating the laws of the land. Therefore, it struck me, as a newly sworn in American citizen that what all Americans should learn from this case is: ignorance of the law does not pardon a criminal. This case should serve as a call for action in order to improve assimilation efforts already in place.